The vast, green grasslands stretch across the impossibly flat plains, a few hazy trees pockmarking the stretched horizon. Every now and then, a small pocket of tokuls, the traditional Sudanese mud and thatched huts, pop-up alongside the dirt road that leads to Pariang, at the heart of Sudan.

Pariang lies in the north of South Sudan’s Unity State, a name that seems rather odd considering the impending independence of the south. In January’s referendum, citizens were asked to vote for either unity or secession; the latter was chosen with nearly 99% of the vote.

It is at the northern-most tip of Unity state that Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the north’s army, have been bombing the town of Jau, lying right on the north-south border-to-be. This lakeside town has been attacked several times by the SAF’s infamous Antonov bombers, which reaped fear amongst the southerners during the bitter, decades-long civil war. The International Organisation for Migration has said that 3700 have so far fled, and many more have “run to the bush”.

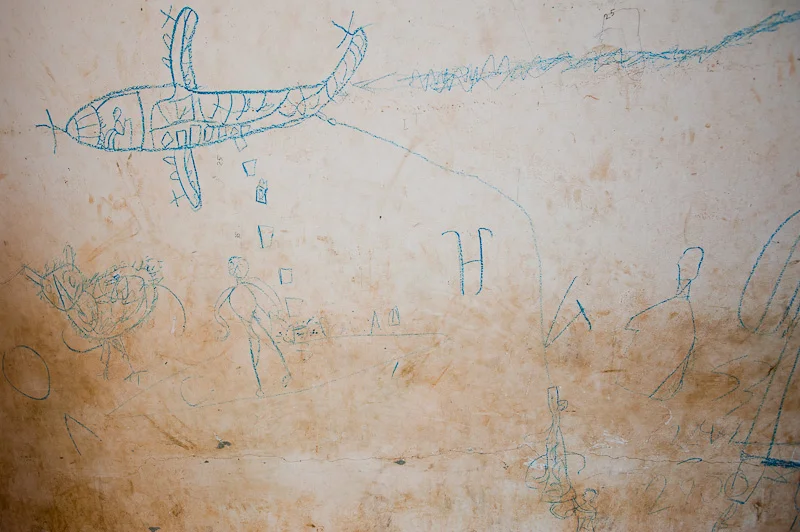

The first bombs fell on Jau on June 10th, and the town has been hit several times since. “Antonovs bombed the area and killed my son” said Thrab Deng, a woman who fled Jau. She spent a day walking through the mud to Pariang, the capital of the county, where she has been for the past week. “We don’t have food here” she says, “I go and beg from people”.

The community in Pariang is doing their best to support the displaced, but have little resources with which to do so. Much of Unity State relies on road links from the north to stock their markets, but these roads have been closed for the past three months. According to market surveys conducted in Bentiu, the state capital, by the World Food Programme, the price of sorghum, a staple for the Sudanese, have doubled in recent weeks. Fuel prices have also rocketed, limiting the transport available to these remote regions, as well as raising commodity prices. Add to that no tarmac roads linking Bentiu and Pariang, the dirt road becomes all but impassable when the rains come. As I drove back from Pariang to Bentiu after an afternoon of rain, one of the two lorries we passed en-route was stuck in the mud. The second, up on axles, changing a blown-out tyre amidst the thick mud.

Thrab is not alone in being short of food, far from home. Taking shelter in a building on the outskirts of town, the fifty or so families staying here all came with virtually nothing, fleeing the bombs. They carried their children during the day-long walk through the mud from Jau to Pariang. “Today we don’t know what we will eat” says Martha, another mother staying there. “We have yet to get assistance from the government or NGOs.”

The World Food Programme, in association with World Vision, an NGO working in Unity State, will soon start distributing food to the most vulnerable, but in this town of little, many will lay claim to that title.

Unity is also the southern state that has received the most returnees from the north, in the build-up to independence, further stretching already limited resources. From late October 2010 to June 21st of this year, nearly 78,000 South Sudanese have come to the state. And over 45,000 are displaced this year in Unity.

But for those fleeing Jau, they live amongst the fear of further bombing from the North. Local officials here say that they can hear the bombing from Pariang, and have seen planes flying over Panyang, a village fifteen kilometres further north. “I am worried that Antonovs will follow us here and bomb Pariang town” says Ayak, a mother of three. Her husband stayed behind in Jau when she fled, and she says that she has not heard from him since she left. “I am worried that my husband may not be alive” she adds.

Col. Mabek Lang Mading, the Commissioner for Pariang County says “I appeal to the international community to condemn the attacks”, asking also for international intervention. The South Sudanese army, the SPLA, has hitherto been relatively restrained in their response to the bombings, possibly fearing that any retaliation could jeopardise their chance for secession come July 9th, the day the South will officially declare independence. Thereafter, this restraint could change. Col. Mading says that “if the SAF are still bombing Jau after 9th July, then we will definitely respond”, reiterating that “we have the right to respond and we must protect it”. This would mean a return to war, but this time between two sovereign nations.

Some, such as Thrab, wish to remain here in Pariang. “I will not go back, no way” she says. But many want to return to their homes, and reunite their families. “When there is no more fighting, I can go back to Jau to see if my husband is still alive” says Ayak. For that to happen, there needs to be an end to the fighting. “We cannot go back to Jau unless there is security there” says Abdullah Ibrahim Suleiman. But with continued bombing, and two states on the verge of war, this security could be a long way off, with many more yet to suffer.