Four-years-to-the-day since I first landed in Goma, a collection of work from Eastern Congo

News and vignettes

Viewing entries tagged

People

Four-years-to-the-day since I first landed in Goma, a collection of work from Eastern Congo

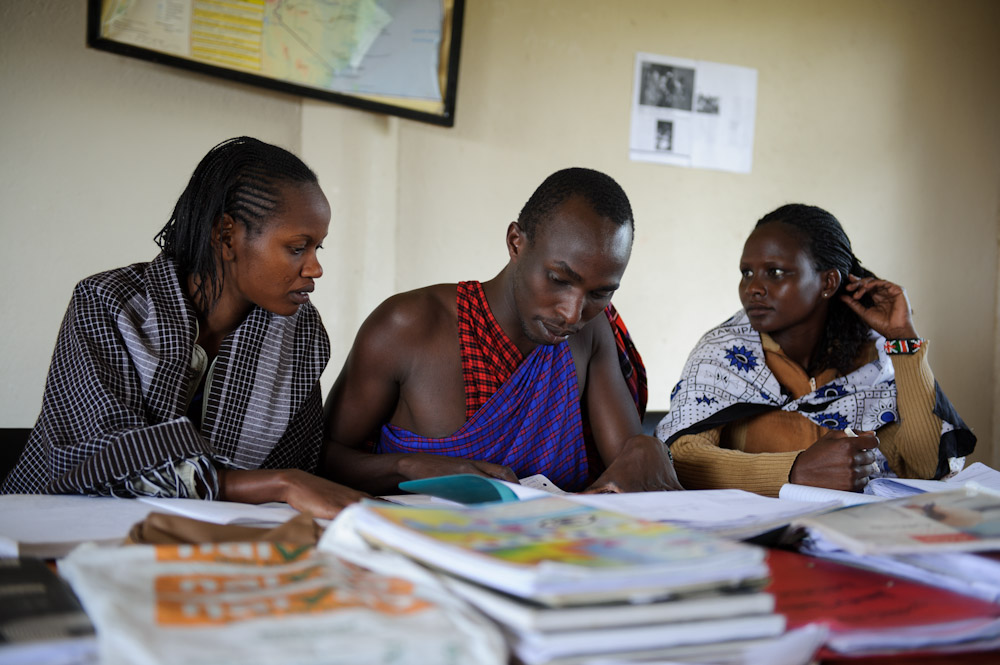

In the Naibosho conservancy, on the edge of Kenya’s Maasai Mara, outreach programmes and entrepreneurial schemes organised through the conservancy are giving new opportunities to young Masai girls and women.

Lorna Kiu, now 15-years-old, comes from a traditional Masai farming family and says that when she was 10, her parents wanted her to get married which would also involve being circumcised. She refused, saying that she wanted to go to school. “I remember it was a need for me to learn.”

Nasirku Rakwa, 22, keeps her own goats. “Traditionally it is only the men who tend to the animals. Now you even get groups of women going out with the livestock” she says.

The outreach programme was established with local tourism partners from three nearby wildlife conservancies. At the Koiyaki Guiding School, young Masai men and women are learning the skills needed to work with tourists, from learning about the wildlife that surrounds them, to how to speak French. Whilst the dark green 4x4s of safaris seem out of place amongst the traditionally dressed Masai, it is the money that the tourism industry creates that goes back into these communities and funds such projects.

The schemes also protect wildlife. Grace Naisenya Ololchoki, an outreach programme coordinator, organises educational trips for women to go and see the conservancies. “Some of them have never seen a lion or elephant” she says. “They learn to live with predators and wild animals, to protect their wildlife.” Women also learn bee-keeping and dairy farming with goats, giving them greater economic independence.

See more on this Al Jazeera slideshow

In the Congolese village of Kiliwa, along the dusty road leading from Dungu, a lone healthcare outpost stands, scarred by fighting, with memories of the Congolese civil war, and of attacks by the Lord’s Resistance Army. To get here, one passes a Congolese army checkpoint. The driver remembers when, a year ago, two soldiers were killed here during an attack by the LRA.

Etched into crumbling walls is graffiti, mixing both supplications to God and images of AK-47s, with a red sort of honey oozing out of holes, left by the hornets that buzz around what constitute the wards.

Much of the local population has left Kiliwa, having fled the area due to attacks by the LRA. And for those that remain, there is a feeling that they have been forgotten. Chronic underdevelopment coupled with near-continuous conflict has degraded the state of health centres in most parts of Haut & Bas Uélé, says an NGO working in the area. “Most clinics lack essential equipments and majority of the health professionals are not properly trained.”

When working with NGOs in the region, one often sees the “successes”: the mosquito nets being handed out, immunisations being injected into the arms of young babies, free, primary health care. But here in Kiliwa, one has a brief glimpse of what it is like away from the fleets of white Land-Cruisers.

A nurse, alcohol on his breath, pricks the finger of an elderly lady to test for malaria. In the opposite room, a lady lies on a stained, bare mattress, a dressing on her leg from an infection brought on following treatment in the centre.

A sense of a people forgotten, or ignored, by their government. The ones who stayed behind.

Soon, the Land-Cruisers will be coming, to provide free health care to “the vulnerable”, and to train health professionals. But that can only ever be a short-term fix. It will help some, but the authorities running the country need to remember who they work for.

A young boy stands with a panga, used for chopping small trees for firewood and making homes, in the Nanzawa camp for internally displaced persons on the outskirts of Dungu in D. R. Congo’s Orientale Province.

Lord’s Resistance Army rebels, led by Joseph Kony, have been attacking civilian populations in Haut and Bas Uélé districts since 2008, resulting in the displacement of over 300,000 people, according to an international NGO working in the region.

I was surprised by the amount of iconography of Aung San Suu Kyi that one could find on the street-side in Myanmar. I knew she was out from her house arrest, and could run for the up-coming elections, but didn’t expect the freedom of expression to result in pictures of her on many street-corners. Here, a portrait of her hangs in a gallery standing in the market named after her father, Bogyoke Aung San, a hero of independence.