The Hurri Hills of Kenya, north of Marsabit and across the Chalbi desert, seemed to be the remotest place on Earth. I hadn’t seen tarmac for days, and small, rocky tracks stretched across the plains and wound their way through the hills.

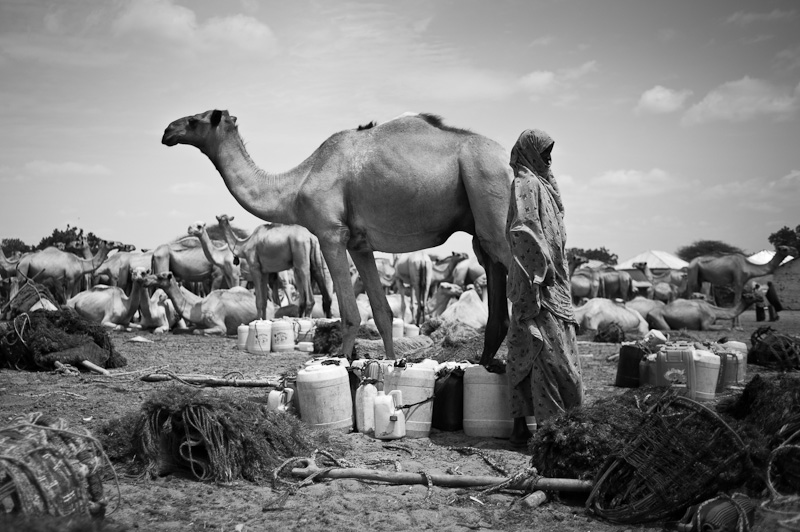

Small communities live nestled in these hills, miles from anywhere. They draw what scarce water there is, where they can. And that water is becoming increasingly scarce with the drought affecting the Horn. They walk with their cattle across the vast plains, in search of pasture. It is rare that they see outsiders in these parts.

Borders mean little up here. An ageing man in one village I visited told me “our nearest water is the other side of those hills”, pointing towards the horizon. The other side of those hills is Ethiopia, a journey they would make daily. The nearest market, a source of produce as well as an outlet for their goats, was also in Ethiopia. No-one holds a passport.